I’m all about incorporating family history with family vacations (my husband, surely, is grateful). This month marks ten years since I embarked on one such vacation. After becoming fascinated with our ancestors who settled in what is now Nova Scotia, my dad and I spent several memorable days exploring what was once Acadie on a quest to learn more about their experiences prior to the Acadian Deportation of 1755-1763.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Nova Scotia was a French colony called Acadia, or, in French, Acadie. The residents were peasants who farmed land reclaimed from the sea and developed peaceful relationships with the natives. After the colony was transferred to British control, the Acadians proclaimed their neutrality. However, during the French and Indian War, the British colonial officers became suspicious that the Acadians might be providing aid to the French. With the support of New England legislators and militia, approximately 11,500 Acadians were forcibly deported from Nova Scotia and the surrounding maritime provinces. As the Acadian men, women and children were ordered aboard ships, their lands were confiscated and their homes were burned to discourage their return.

After reaching Nova Scotia, my dad and I made our way from Halifax to the Grand-Pré National Historic Site. Here, a church stands to commemorate the site where Colonel John Winslow rounded up the local men and boys to declare the terms of the deportation. A statue of Evangeline, Longfellow’s fictional Acadian heroine who became separated from her lover, stands here as well. We were fortunate to visit Nova Scotia in 2004, the 400th anniversary of French settlement in North America, as we were able to see a musical performance of Evangeline in Pointe-de-l’Église.

After reaching Nova Scotia, my dad and I made our way from Halifax to the Grand-Pré National Historic Site. Here, a church stands to commemorate the site where Colonel John Winslow rounded up the local men and boys to declare the terms of the deportation. A statue of Evangeline, Longfellow’s fictional Acadian heroine who became separated from her lover, stands here as well. We were fortunate to visit Nova Scotia in 2004, the 400th anniversary of French settlement in North America, as we were able to see a musical performance of Evangeline in Pointe-de-l’Église.

We also paid a visit to the Port-Royal National Historic Site, located at the site of the original 1605 habitation that was France’s first successful settlement on North American soil. Port Royal held a wealth of information about this hardy settlement, and it was interesting to explore. We were particularly amused to find an artist’s rendition of one of our more illustrious ancestors, Louis Hebert, within the habitation; he served as an apothecary there before venturing on to New France.

We also paid a visit to the Port-Royal National Historic Site, located at the site of the original 1605 habitation that was France’s first successful settlement on North American soil. Port Royal held a wealth of information about this hardy settlement, and it was interesting to explore. We were particularly amused to find an artist’s rendition of one of our more illustrious ancestors, Louis Hebert, within the habitation; he served as an apothecary there before venturing on to New France.

We spent another afternoon strolling through the beautiful Annapolis Royal Historic Gardens, where we were able to explore a reconstruction of a typical 1671 Acadian home. The comfortable cottage featured a thatched roof and beds that each had their own cozy cupboard doors. It was fun to see how the Acadians lived as well as what they ate, as we did when we stopped by the charming farmhouse restaurant Chez Christophe for some excellent seafood and rappie pie, an Acadian specialty.

We spent another afternoon strolling through the beautiful Annapolis Royal Historic Gardens, where we were able to explore a reconstruction of a typical 1671 Acadian home. The comfortable cottage featured a thatched roof and beds that each had their own cozy cupboard doors. It was fun to see how the Acadians lived as well as what they ate, as we did when we stopped by the charming farmhouse restaurant Chez Christophe for some excellent seafood and rappie pie, an Acadian specialty.

The Fort Anne National Historic Site overlooks the Annapolis Basin, which is from where at least one of our ancestors, Joseph Michel, was deported. Fort Anne saw conflict in the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, and the War of 1812, and it was another well-kept and informative site. We were a bit thrown off when we thought we recognized the historical interpreter as having also been at Port Royal, but as it turned out, the two men were twin brothers, and apparently used to double takes!

The Fort Anne National Historic Site overlooks the Annapolis Basin, which is from where at least one of our ancestors, Joseph Michel, was deported. Fort Anne saw conflict in the French and Indian War, the American Revolution, and the War of 1812, and it was another well-kept and informative site. We were a bit thrown off when we thought we recognized the historical interpreter as having also been at Port Royal, but as it turned out, the two men were twin brothers, and apparently used to double takes!

Last but not least, we made a point of walking on some of the land where our ancestors had farmed centuries before. Nova Scotia, as it turns out, is well prepared for this type of tourism, with maps at the ready – both paper and of the trail side marker variety – indicating where the properties affiliated with different Acadian surnames were once located. Nova Scotia remains quite rural, and it was wonderful to be able to picture our ancestors’ lives so clearly with much of the land still undeveloped.

Last but not least, we made a point of walking on some of the land where our ancestors had farmed centuries before. Nova Scotia, as it turns out, is well prepared for this type of tourism, with maps at the ready – both paper and of the trail side marker variety – indicating where the properties affiliated with different Acadian surnames were once located. Nova Scotia remains quite rural, and it was wonderful to be able to picture our ancestors’ lives so clearly with much of the land still undeveloped.

After seeing a few more sites in Nova Scotia, my dad and I returned home laden with pictures, maps, brochures, books, recipes, and Acadian and Cajun music, as well as an Acadian flag and the occasional unintentional burst of an Acadian accent. Of course, it was also all too easy to see why our ancestors would not have wanted to leave their homeland, and why some Acadians underwent great hardship in order to return.

Although our direct ancestors, who were deported to Massachusetts, ultimately settled in Quebec, it is certainly telling that they named their new home l’Acadie.

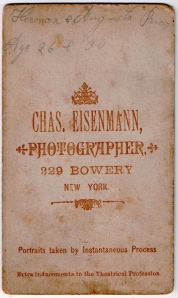

The photograph was taken by Charles Eisenmann, a photographer in the rough-and-tumble Bowery district of New York City who frequently photographed performers such as these.5 Although he was employed as a photographer in the city as early as 1876,6 he didn’t make the move to 229 Bowery, the address stamped on the back of this photograph, until 1879 or 1880.7 Eisenmann remained at this location at least until 1883.8

The photograph was taken by Charles Eisenmann, a photographer in the rough-and-tumble Bowery district of New York City who frequently photographed performers such as these.5 Although he was employed as a photographer in the city as early as 1876,6 he didn’t make the move to 229 Bowery, the address stamped on the back of this photograph, until 1879 or 1880.7 Eisenmann remained at this location at least until 1883.8