Jordan Stilley was a southern Illinois settler of the early nineteenth century who had a family of twelve children. His name appears on only a smattering of records, and at a time and place where efforts to keep vital records were scant if not entirely nonexistent, developing a picture of his life is not unlike attempting to assemble a jigsaw puzzle with only a few of the pieces available.

Born in either 1797 or 1799 in Hyde County, North Carolina, Jordan Stilley was one of nine known children of Hezekiah Stilley and Sarah Davis. No record exists of Jordan’s birth, and no record has been located that documents the marriage of his parents; this information has been pieced together thanks to transcriptions of a faded nineteenth-century family Bible by the late genealogist Peggy (Stilley) Morgan, the 1802 will of Jordan’s maternal grandfather, and early census records.

Jordan likely made his first appearance in federal records as a tick mark in the 1800 United States census. Hezekiah Stilley was recorded as the head of a household of eight individuals in Hyde County, North Carolina that included a male and a female between the ages of 26-44, two males between the ages of 10-15, three males under the age of 10 (one, presumably, being Jordan), and one female under the age of 10.

Before Jordan was ten years old, he had trekked eight hundred miles west with his parents and siblings as well as members of his extended family. Their destination was the Illinois Territory, and it was there that his father’s name appeared on a petition for three hundred and twenty acres of land in what is now Cave-in-Rock Township, Hardin County, Illinois. This petition indicated that Hezekiah, among others, had been squatting there prior to a legislative act which took place on 03 March 1807.

Cave-in-Rock, located on the Ohio River, would have been a rough place for a child to grow up, as it was known at the time as a hotbed of river pirates, outlaws, and highwaymen. In the winter of 1811-1812, when Jordan was twelve years old, he would have felt the rumblings of the New Madrid earthquakes, the epicenter one hundred-some miles away. Did his family’s frontier home survive, or was destruction such that they were forced to rebuild or relocate?

In December of 1812, Jordan’s eldest brothers—Davis, John, and Stephen, all of whom were over the age of twenty-one—are believed to have signed a petition put forth by residents of the Big Creek Settlement in Illinois Territory. Jordan’s father’s name was not included on this petition; if he were still living, which he may not have been, he would have been around fifty years of age at this time.

Jordan Stilley made his first appearance in the United States census by name in 1820 as “Jourdan Stilly,” head of a household in the area of Frankfort, Franklin County, Illinois that included one male and one female between the ages of 16-25 and one female under the age of 10. The age of the adults and presence of only one young child suggests that Jordan was relatively recently married, and it is notable that he was enumerated next to the household of his brother Davis Stilley. Also notable is the presence of both a William Farris and a John Farris in Franklin County. Although the county’s marriage records are incomplete, it is believed that Jordan Stilley married Phoebe Farris here circa 1818.

According to recent research, Phoebe Farris, whose name is known only from the obituary and cemetery records of her youngest daughter, appears to have been the daughter of Virginia-native William Farris and his presumed wife Mary “Polly” Bunnell. Genealogist George J. Farris has indicated that all of the children of brothers William Farris and John Farris have been identified with the notable exception of one daughter of William, who was acknowledged via tick mark in the 1810 United States census in Green County, Kentucky. This daughter would have been born between 1797-1800—and it now seems likely that this daughter was Phoebe, as she lived in the right place at the right time to have become the wife of Jordan Stilley. DNA connections between Farris/Bunnell and Stilley/Farris descendants tentatively support this relationship.

Jordan relocated with his family at least once again between 1820 and 1830, at which time he was enumerated in the United States census in Washington County, Illinois. His household now included one male and one female 30-39, two males under 5, one male 5-9, one female under 5, one female 5-9, and one female 10-14—a total of two adults and six children. His brothers Davis and Hezekiah resided nearby. Little is known about Jordan’s life in the next decade save for the fact that in January of 1838, there is record of his purchase of one bay mare, one yoke of oxen, one wagon, one sorrel mare, and one colt from his brother Davis Stilley, who operated a mill.

In 1840, Jordan remained in Washington County where he was enumerated in the United States census with a household that included one male and one female 40-49, one male under 5, one male 5-9, two males 10-14, one male 15-19, one female under 5, one female 5-9, one female 10-14, and one female 20-29. This equates to nine children at home; his two eldest daughters were known to have married before 1840 and were no longer living at home. The household of Mary Stilley, who was the widow of his brother Hezekiah, was recorded next on the census, and, according to The History of Washington County, Illinois, both Jordan and Mary were constituent members of the Concord Baptist Church at the time of its founding in 1841. The Baptist tradition was strong in the Stilley family; Jordan’s paternal uncle was Elder Stephen Stilley, who was a missionary and founder of the Big Creek Baptist Church, not far from Cave-in-Rock, in 1806.

Tragedy befell Jordan’s family when his son, also named Hezekiah, enlisted to serve in the Mexican-American War and died in Buena Vista, Mexico, in the spring of 1847. The following year, Jordan was involved in a bounty land transaction for one hundred and sixty acres of land in Pettis County, Missouri; this was due to the service of his late son, who died without wife or children, and confirms that “Jourdan Stilley” was “father and heir at law of Hezekiah Stilley deceased, late a Private in Capt. Coffey’s Compy. 2nd Regt. Illinois Vols.”

Jordan must have lost his wife Phoebe at some point between 1844-1850; their youngest child was born in 1844, and on 19 March 1850, Jordan married Malinda (White) Vaughn, a young widow who had a four-year-old child of her own. Oddly, Jordan and Malinda do not appear in the 1850 United States census with Jordan’s youngest children nor her young son, and some of Jordan’s children can be found living in the households of their adult siblings. Although no will has been located, it is believed that Jordan died circa 1854. It was in that year that Jordan’s apparently disabled daughter Sarah Ann—who was documented as being “idiotic” and “insane” in the 1860 and 1870 United States censuses—was entered into the guardianship of an older brother, and Jordan himself signed with an X. In 1857, Sarah Ann, “minor heir of Jordon Stilley,” was entered into the guardianship of Ebenezer Davis of Washington County, Illinois.

Based on research by genealogists William D. Stilley and the late Dr. Bernard “Bud” Hall, as well as information compiled from census records, land records, newspapers, military pension files, and personal correspondence, the following twelve individuals are believed to be the children of Jordan Stilley and his first wife, Phoebe Farris:

- Nancy (Stilley) Holman Edwards Hall, born 22 June 1819, died 21 October 1898

- Hester Ann (Stilley) Rogers, born about 1821, died before 1860

- Hezekiah Stilley, born about 1823, died 19 April 1847

- William J. Stilley, born about 1825, died about 1857

- Robert M. Stilley, born about 1827, died 1856

- Mary A. (Stilley) West, born about 1829, died March 1870

- Jeremiah Stilley, born about 1832, died 1876

- Mary Jane (Stilley) Dennis, born 16 March 1835, died 31 October 1914

- James Albertus Stilley, born 18 June 1837, died 15 December 1890

- Sarah Ann Stilley, born about 1839, died after 1870

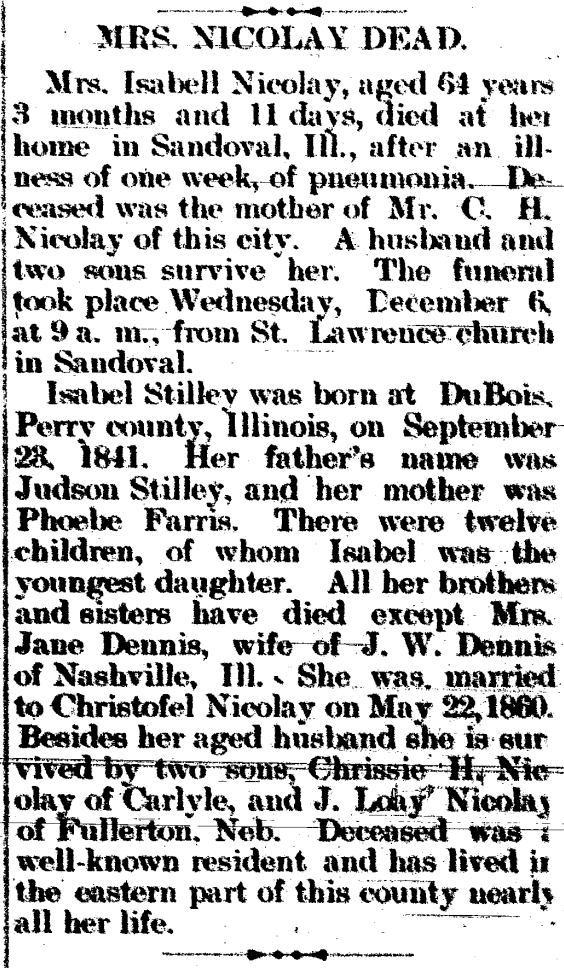

- Isabelle (Stilley) Nicolay, born 23 September 1841, died 03 December 1905

- Wilson Stilley, born 22 February 1844, died 18 February 1899

The birth order of the children is not set in stone due to the absence of birth dates of more than half; however, there is some evidence of common naming conventions having been followed, such as the potential eldest son being named for the paternal grandfather and the potential second eldest son being named for the maternal grandfather. In any case, it is not a linear process to establish familial relationships between individuals when there is an absence of vital records, and the twelve inferred children of Jordan Stilley make for a particularly tangled web.

The most definitive piece of evidence regarding the Stilley family structure is a 1905 obituary of Isabelle (Stilley) Nicolay which names her as the youngest daughter of the twelve children of “Judson Stilley and Phoebe Farris” and as a sister of Mary Jane (Stilley) Dennis. However, a Marion County, Illinois cemetery index lists Isabelle’s parents as Jordan Stilley and Phoebe Farris. Considering the lack of evidence of the existence of a Judson Stilley in southern Illinois in the nineteenth century, it stands to reason that the name Judson was printed in her obituary in error and should have been Jordan.

Another striking piece of evidence is a handwritten letter from a son of Wilson Stilley to his first cousin, a son of Nancy (Stilley) Hall, after Wilson’s death in 1899, which establishes that Nancy and Wilson were brother and sister, and that “Aunt Bell” (Isabelle), “Aunt Jane” (Mary Jane), and “Uncle Jerry” (Jeremiah) were their siblings as well. Some of these connections are also supported through the obituaries of both Wilson Stilley and Nancy (Stilley) Hall, which link them as siblings of Mary Jane (Stilley) Dennis, as well as through newspaper social columns, which connect Nancy, Mary Jane, and Isabelle as sisters. In those it was noted that Isabelle (Stilley) Nicolay visited “her sister” Nancy (Stilley) Hall in Saline County, Kansas in 1890 and 1892, as well as “her sister” Mary Jane (Stilley) Dennis in Washington County, Illinois in 1903.

Federal records also provide clues. The aforementioned 1848 bounty land record confirms that Hezekiah Stilley, who died while serving in the Mexican-American War, was the son of “Jourdan Stilley.” The Civil War pension files of both Wilson Stilley and James Albertus Stilley include handwritten depositions that link Wilson, James, Isabelle (Stilley) Nicolay, and Hester (Stilley) Rogers as siblings.

In addition, an 1854 Washington County, Illinois guardians’ bond held at the Illinois Regional Archives Depository at Southern Illinois University places Sarah A. Stilley, a minor, into the guardianship of William J. Stilley, presumably her brother, in a document signed also by “Jorden Stilley” and witnessed by Robert West, presumably the husband of her sister Mary A. Stilley. An 1857 court record from the same county names Sarah Ann Stilley as a “minor heir of Jordon [sic] Stilley, late of said county, deceased.”

It is highly unlikely that a singular smoking gun, so to speak, that clearly defines the relationships between Jordan Stilley, his wife, and all of his children, will ever be revealed, due to both scant documentation and an 1843 fire at the Franklin County, Illinois courthouse that destroyed many early records. However, their story has been slowly but surely puzzled together through a range of sources and an understanding of the norms of the time that make it possible to infer relationships with a reasonable level of confidence. To have raised twelve children to adulthood on the Illinois frontier was no small feat, and Jordan and Phoebe (Farris) Stilley, though their graves are unmarked and the details of their stories lost to time, are worth remembering.

Copyright © 2025 Melanie Frick. All Rights Reserved.

Continue reading