Sometimes, there’s more to the story.

Eleven years ago, when I first wrote about the accidental death of Kansas pioneer George W. Fenton, the number of historic newspapers that were readily available to search online was still relatively slim. I was aware that George’s death had made the news—but at that time, I was not yet aware that several differing accounts of the incident had circulated, nor that the news had spread throughout Kansas and beyond.

George W. Fenton—a son of English immigrants who was orphaned at the age of ten when his father perished in the Civil War—had overcome his difficult childhood in Ohio and Illinois and settled down to a farmer’s life near Gypsum Creek in Saline County, Kansas. He had been married for seven years and was the father of three young daughters when, at the age of twenty-eight, he was accidentally shot and killed by his brother-in-law.

As it turned out, George had had another brush with misfortune with a firearm only days before his death. On 02 October 1880, the Salina Herald reported: “Mr. George Fenton had his eyes badly burned by the premature discharge of a gun last week. He is now able to see out of one of them, and hopes they are not seriously injured.”

Perhaps George was still taking things easy on the afternoon of Sunday, 10 October 1880, when he and his family visited at the homestead of his mother-in-law, Nancy (Stilley) Hall. However, that is when tragedy struck. The following Thursday, the Saline County Journal reported:

A Sad Accident. A very painful accident happened last Saturday which resulted in the death of George Fenton, of Gypsum creek. Mr. Fenton with his family was upon a visit to his mother-in-law, who resides about eighteen miles south-east of town, and with whom was residing “Bud” Hall, her son and brother-in-law of Mr. Fenton. During the afternoon while those two persons were engaged in some boyish pranks, Hall playfully presented a shot gun at Fenton (which Hall supposed was unloaded), cocked it and snapped the hammer. A charge of shot was lodged in Fenton’s breast, which proved his death wound. He lived for only an hour after the shot. He leaves a wife and three children. How the charge came in the gun is a mystery, as everybody about the house supposed the gun to be unloaded. Hall is nearly distracted over the result of his carelessness. The brothers-in-law were the best of friends—no trouble ever having occurred between them. The occurrence was so clearly a case of accidental shooting that no coroner’s jury was summoned. Mr. Frank Wilkeson came to town for surgical aid and Dr. Switzer hastened quickly to the scene of the accident, but arrived after Fenton’s death. The moral to be drawn from the careless habit of handling “unloaded guns” is too plain to be commented upon here. Will people never learn better?

The Saline County Journal, 14 October 1880

On the same day that the news was first reported in The Saline County Journal, the McPherson Republican printed the following:

Again we are called upon to listen to the sad results of carelessness with fire-arms. On Sunday, October 10, in the south-eastern part of Saline county, Mr. George Fenton was accidentally shot by his brother-in-law, Bud Hall. They were both playing with the children, little dreaming of the great calamity that was about to befall one of them. Mr. Hall wishing his gun, reached through the door, and not looking at what he was taking in his hand, took hold of a gun that belonged to a person who was visiting him. Thinking it was his own gun and knowing that it was not loaded, he drew it towards him more carelessly than he would have done had he known it was not his own gun. The hammer of the gun struck against the door side and discharged it; the shot striking Mr. Fenton in the left breast and ranging upward lodged under the shoulder blade. Mr. Andrew Sloop, who had passed a moment before, was called back, and sent post haste to Roxbury for a physician. Doctor Zawadsky hastened at the call, but it was of no avail. The results were fatal, he having expired about one and a half hours after the accident, and before the Doctor arrived. Mr. Fenton leaves a wife and three children to mourn his sad loss. Mr. Hall is almost crazed, and does nothing but rave and call with endearing entreaties to the departed one. All the neighbors sympathize with the distressed family, as they show by their willing assistance. – E. October 11, 1880

McPherson Republican, 14 October 1880

Perhaps Bud had not, in fact, been so cavalier as to actually point a gun at George. The McPherson Republican account eliminates some of the blame he might otherwise have assumed by explaining that the gun—which belonged not to Bud but to an unnamed visitor—discharged accidentally when Bud reached for it behind a door. The account also informs us that medical assistance was sought not only by Frank Wilkeson, who went for Dr. Switzer of Salina, but also by Andrew Sloop, who fetched Dr. Zawadsky of Roxbury. However, both physicians arrived after George’s death, which was said to have occurred either one or one and a half hours after he was shot.

The following day, The Canton Monitor printed the following version of the events:

“We are informed by Mr. Banks, of Roxbury, that an accident occurred about five miles north of that place, by which Mr. George Fenton lost his life. The way it happened was this: Mr. Hall, a brother-in-law of Mr. Fenton, went to see him, Fenton, last Sunday. Mr. Hall was sitting in the door watching the children playing with the dogs, when he told one of them, jokingly, that he would shoot his dog, and at the same time reaching behind the door to get a shotgun, where two were standing. As he was taking one, the hammer of the gun caught some way, causing it to go off, the charge striking Mr. Fenton in the breast, killing him almost instantly. The shooting was entirely accidental, as they were the best of friends. Mr. Hall has went crazy from the accident, thus leaving two families as good as fatherless.

The Canton Monitor, 15 October 1880

This account contradicts the first in that it suggests that Bud was visiting George, when in fact The Saline County Journal was most likely correct that George was at the home of his mother-in-law, which is where Bud also resided with his family. (Frank Wilkeson, who went for the doctor, was a neighbor of the Halls.) This account also states that George died almost instantly, which is unlikely as otherwise there would have been no call to send for a doctor. However, The Canton Monitor does give a very specific and perhaps more believable account of what initiated the chain of events that resulted in George’s death. Like in the McPherson Republican, it is indicated that George and Bud were playing with the children at the time of the accident, but The Canton Monitor goes on to say that Bud was joking with the children that he would shoot his dog. (At a time when “mad dogs” were a more commonplace concern and livestock needed to be protected, this joke may have come across as slightly less alarming than it would to a modern audience!) Furthermore, the account agrees with the McPherson Republican that there was more than one gun standing behind the door, and that the hammer of the gun was caught in a way that caused it to unintentionally fire in George’s direction.

The next day, the Salina Herald printed another account of the events of October 10, more closely following the version published in the McPherson Republican and The Canton Monitor:

Sad Accident. Another sad result from the careless handling of guns occurred on Gypsum last Sunday. It appears that Geo. Fenton, living on the west branch of Gypsum creek went over to visit his mother-in-law, Mrs. Nancy Hall, who lived a short distance from him. While there himself and brother-in-law Bud. Hall were talking of hunting. Their gun was standing behind the door. Bud. Hall reached for it to shoot a dog, when the hammer caught in some way, and discharged the load in Fenton’s breast just above the heart. Mr. Wilkinson being near was informed and immediately came in for a physician, but whose service were too late, as Fenton lived only about an hour. The shooting was purely accidental, the thing to be condemned being the careless handling of firearms. Death often appears to be no warning, and almost daily is recorded sad accidents like this. Geo. Fenton was 27 years old and leaves a wife and three children to mourn his loss. He was buried Monday in McQuary’s graveyard on Gypsum Creek.

Salina Herald, 16 October 1880

The same edition of the Salina Herald also noted the following:

Mr. George Fenton, who was killed on Sunday last by the accidental discharge of a gun, was buried on Tuesday. There was a large attendance at the funeral and much sympathy expressed for the widow and her three children so suddenly bereaved of a husband and father. This adds one more instance of the criminal folly of playing with fire arms under any circumstance. Guns and [sic] playthings, but very serious matter of fact implements that carry death and destruction in their path whether accidentally or intentionally used.

Salina Herald, 16 October 1880

News of George’s death reached the Topeka papers before the end of October, and in November, it was reported in Wichita as well as in the Daily Illinois State Register in Springfield, Illinois: “George Fenton, a former resident of Buckeye Prairie, late of Saline county, Kansas, was accidentally shot and killed last week through the criminal carelessness of a a brother-in-law, who snapped a gun at him, not knowing that it was loaded.”

Elithan Davis “Bud” Hall did apparently recover from the grief and guilt he experienced at the loss of his brother-in-law and close friend. He went on to raise a family a family of four children and lived out his life on the Hall Homestead in Gypsum. A photograph of him as an older man with a grandchild by his side shows him with a kindly expression, and the laughter lines around his eyes make it easy to imagine him as a good-natured, fun-loving young man whose attempt at a joke went awry.

However, George’s young widow, Sarah, may never have fully recovered from the trauma of the loss of the young man she had married at the age of sixteen. Just twenty-three when she was widowed, she would remarry not once but three more times, with each marriage ending in divorce.

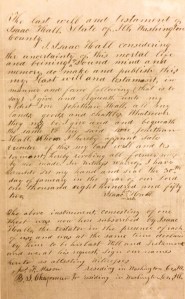

It is interesting that no account makes clear whose gun it was that was left loaded. A final report of the inquest held stated the following:

On Oct. 10, 1880, justice of the peace E.W. Mering was summoned to the home of E.D. Hall “near Frank Welkeson’s farm” to ascertain the circumstances stances of a man’s death. In the event that the county coroner could not attend an investigation (which turned out to be the case), Mering named six citizens to serve as jury: John C. Fahring, John M. Crumrine, Simeon Ellis, Jerome Swisher, D.C. Williams and M.M. Root.

The next day when the inquest was held at the Hall place, Mehring subpoenaed the following witnesses: W. C. Jackson, Alonzo Gosso, Mrs. William Stahl, Mrs. E.D. Hall, Elisha Davidson and James Gaultney. All appeared to testify except Elisha Davidson, who was sick.

Witnesses revealed that George Fenton was shot in the chest by a double barreled shotgun at two in the afternoon of the previous day. The gun had been in the hands of E.D. Hall, Fenton’s brother-in-law. The shooting was ruled accidental.

Whether the double barreled shotgun in question belonged to Bud, George, or one of the witnesses—other neighbors and close kin—who were present at the Hall home that October afternoon is ultimately unknown, but as the gun was in Bud’s hands, he bore full responsibility for the accident.

Copyright © 2024 Melanie Frick. All Rights Reserved.

Continue reading