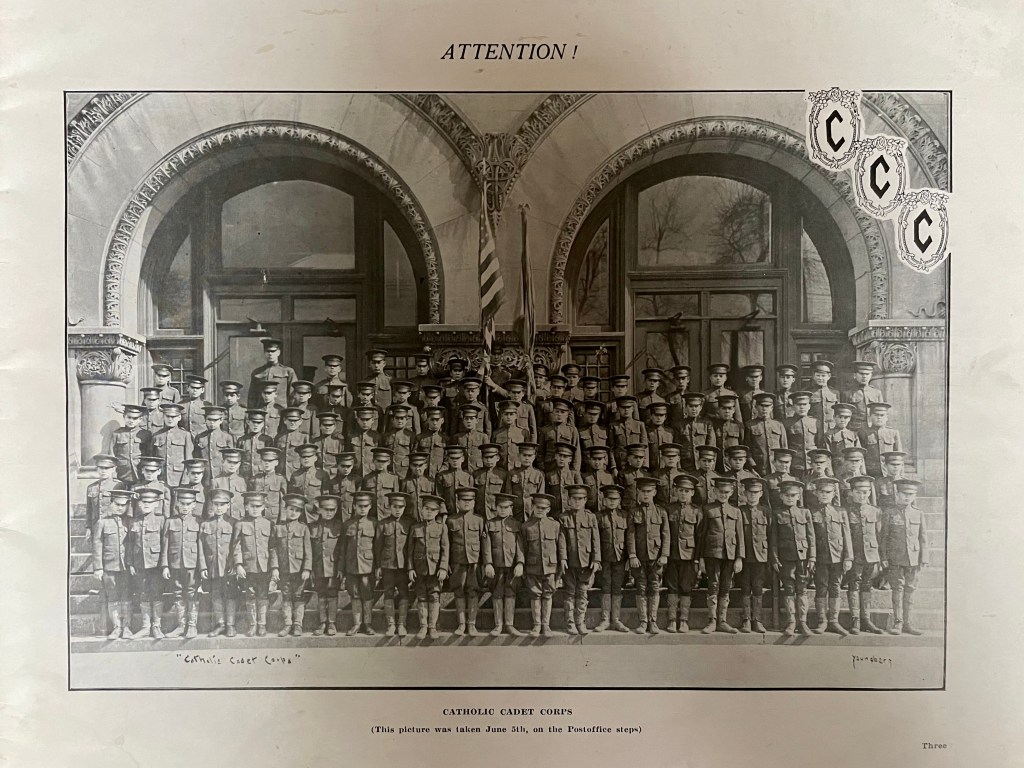

In the summer of 1916, Gerald “Jerry” Adam of Sioux City, Woodbury County, Iowa, celebrated his eighth birthday. Shortly thereafter, he became a charter member of the city’s newly-established Catholic Cadet Corps under the leadership of Reverend Henry A. Janse, Reverend Thomas M. Parle, Sergeant C. A. Butler, and Charles Parsons.

Gerald Joseph Adam and the Charter Members of the C.C.C. (Gerald pictured second row, second from right), 1917 Year Book of the Catholic Cadet Corps (Perkins Bros. Co. : Sioux City, Iowa, 1917); privately held by Melanie Frick, 2023. Collection courtesy of David Adam.

“The Catholic Cadet Corps was organized for the Catholic boys of Sioux City. It is now a citywide organization, and at the present time has a membership of 170. Companies are being formed in the various parishes of the city, so that all the Catholic boys of the city can enjoy the benefits of the C.C.C. For years the need of some such organization has been felt to solve the ‘boy problem.’ Until recently our Catholic boy had no organization of his own and experience has taught us that many of our boys drifted into the Y.M.C.A. on that account.

The Y.M.C.A. is a protestant organization in which our boy is not welcome, in which he can neither vote nor hold office and in which it is constantly insinuated that he is not even a Christian. Naturally this environment is not conducive to the best interest of our boy. The C.C.C. movement was inaugurated with the purpose of giving the Catholic boy surroundings which are in harmony with his faith. A tremendous amount of work has been done to make the C.C.C. attractive, instructive and helpful.”

1917 Year Book of the Catholic Cadet Corps

As a member of the Catholic Cadet Corps, Jerry would have participated in military drills and athletics, marched in parades and decorated the graves of Civil War veterans. He may have been among the group of young cadets who sang “America” at a local theater on Decoration Day 1917 to much applause. The C.C.C. also organized an ambulance corp that took part in numerous aid efforts, and afforded recreational opportunities for its members such as hiking, picnicking, and swimming at the nearby Trinity College.

Catholic Cadet Corps, June 5, 1917 (Gerald Adam pictured second row, sixth from right), 1917 Year Book of the Catholic Cadet Corps (Perkins Bros. Co. : Sioux City, Iowa, 1917); privately held by Melanie Frick, 2023. Collection courtesy of David Adam.

Perhaps most significantly, the Catholic Cadet Corps may have provided Jerry with a sense of community and belonging at a place and time when Catholicism was not necessarily mainstream. “Boys of the C.C.C. are not ashamed of being Catholics—they are proud of it in this free land of the U.S.A.” The 1917 Year Book of the Catholic Cadet Corps made clear that uniforming each young member in a tailored wool suit was an intentional choice. “The fact that the Cadets have the best uniforms in the city makes them think more of their personal appearance, increases their self-respect and has a good influence on their every day lives—they strive to be as good as they look. The boys wear their uniforms to school. This places all the boys on the same level—no distinction between rich and poor—all are Cadets and all try to do their best in school.” Jerry even wore his uniform for a family photograph believed to have been taken circa 1916.

It is not known how long Jerry might have been involved with the Catholic Cadet Corps, but the year he turned ten was a tumultuous one for him. Not only was 1918 marred by war and a global pandemic, but his father was away for long stretches of time due to his employment at a naval shipyard, and then, tragically, his younger brother died at age five following a horrific accident. Jerry was left an only child with a grieving mother and a father occupied with the war effort; it can well be imagined that the leadership and friendship offered by the C.C.C. may have filled a void for him at this time.

Jerry would not be a lifelong Catholic, but his experiences in the Catholic Cadet Corps may have influenced him regardless. At the age of eighteen, he joined the Marine Corps Reserve, and at twenty, he and his bride—although she was not Catholic—were married by Reverend Le Cair of St. Jean Baptiste Catholic Church in Sioux City. Although Jerry’s involvement with the Catholic church waned after that point, he continued to be actively involved in his community through fraternal organizations, as a Little League coach, and as a businessman and entrepreneur. As for Sioux City’s Catholic Cadet Corps, the wartime years seem to have been its heyday and any mention of the organization in the local newspaper dropped off within a few years thereafter.

Copyright © 2023 Melanie Frick. All Rights Reserved.

Continue reading