Roy Louis Christian Walsted, the son of Jens and Kathrine (Christensen) Walsted, was just six years old in 1917 when a wave of infantile paralysis, or polio, swept his hometown of Sioux City, Iowa. He became seriously ill; although the details of his experience are not known, polio can cause flu-like symptoms and, in serious cases, muscle weakness and paralysis that can lead to death. Indeed, several deaths had been reported locally—and many more across the state—by the time the Sioux City Journal printed news of Roy’s anticipated recovery:

SICK AND INJURED | Roy Walstead, 6-year-old son of Mr. and Mrs. James Walstead, 406 South Helen avenue, Morningside, is expected to recover completely from an attack of infantile paralysis, according to the attending physician. The boy is able to walk alone now and in six months he is expected to have recovered entirely. If recovery is complete it will constitute one of the few cases on record, according to the physician.

Sioux City Journal, 14 September 1917

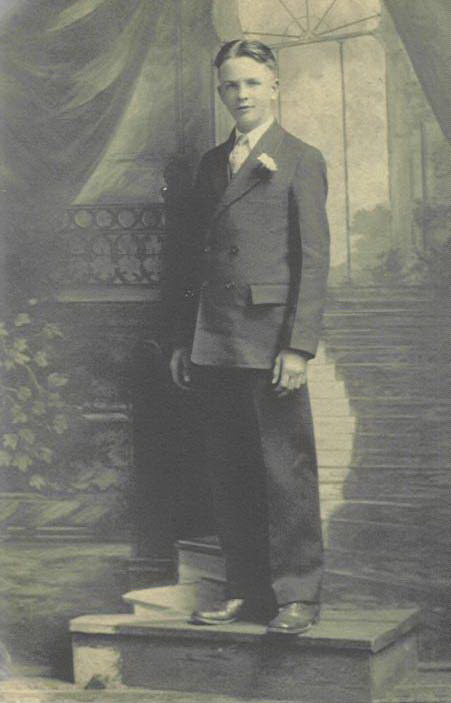

Roy did recover from his bout of polio, although not completely. His left leg was left shorter than his right, resulting in a lifelong limp, and it has been said that his younger brother—who was born just two months after Roy’s illness was reported in the newspaper—was his defender when he faced bullies. While his impaired gait may have discouraged him from athletic pursuits, local news clippings point to other activities that occupied Roy’s leisure time. In 1925, as he entered his teen years, he was a member of Boy Scouts, and he must also have been devoted to his studies as he made the honor roll at East Junior High School in Sioux City that same year. The following year, when Roy was fourteen, he moved with his family to the Logan Square neighborhood of Chicago where his paternal uncle lived. Roy was confirmed at the Gethsemane Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church, located at 2624 Fairfield Avenue, in June of 1926, when he was fifteen, and he most likely completed his second year of high school the following year before entering the workforce.

By the time he was eighteen, Roy had returned to his native Sioux City while his parents and younger brother remained in Chicago. He at first boarded with relatives and within a few years worked his way up from being an office boy at a hardware store to a clerk at the Sioux City Gas & Electric Company. In his spare time, he was active in the Young People’s Society of Our Savior’s Lutheran Church, which conducted its services in Danish, and a 1930 newspaper account reported that he hosted his fellow young congregants at his home at 900 Morningside Avenue. In 1932, as a member of the Sioux City Youth Council, he acted in a biblical drama entitled The Prodigal Son. This was not his only performance that year: he also sang the solo “I Love You Truly” at the twenty-fifth wedding anniversary of his maternal aunt and uncle in Storm Lake, Iowa.

The only sport that Roy was known to have dabbled in as a young man was golf, his name appearing as a participant in a few casual tournaments involving employees of the Sioux City Gas & Electric Company throughout the 1930s. When the time came for him to register for the draft in 1940, the draft card reported that Roy, who was slight of build at five feet eight inches and one hundred twenty-five pounds, had the identifying characteristic of “left leg shorter than right due to Infantile Paralysis.”

Roy married Frances Marie Noehl on 17 January 1934, and their first of seven children was born in Sioux City the following year. Polio outbreaks continued to recur, with nearly one thousand cases reported in Iowa in 1940 and a dramatic peak in 1952 when Iowa saw 3,500 cases, a quarter of which were in Sioux City. Roy and Frances had just welcomed their youngest child in February of that year and they must have been terribly afraid that one or more of their children would be taken ill. Doctors, nurses, and iron lungs were flown to Sioux City in the midst of the outbreak, one of the worst in the nation, and 16,500 children there were part of a gamma globulin vaccine trial that ultimately offered only short-term protection against polio.

However, hope was on the horizon. In 1954, the Salk vaccine trial took place and was deemed a success, and in 1955 the vaccine was made available to the public. The Walsted children were vaccinated at a clinic held at St. Boniface Catholic Church, and fears were finally alleviated.

Copyright © 2026 Melanie Frick. All Rights Reserved.

Continue reading